Case Study | Embedding a System to Protect Patient Safety

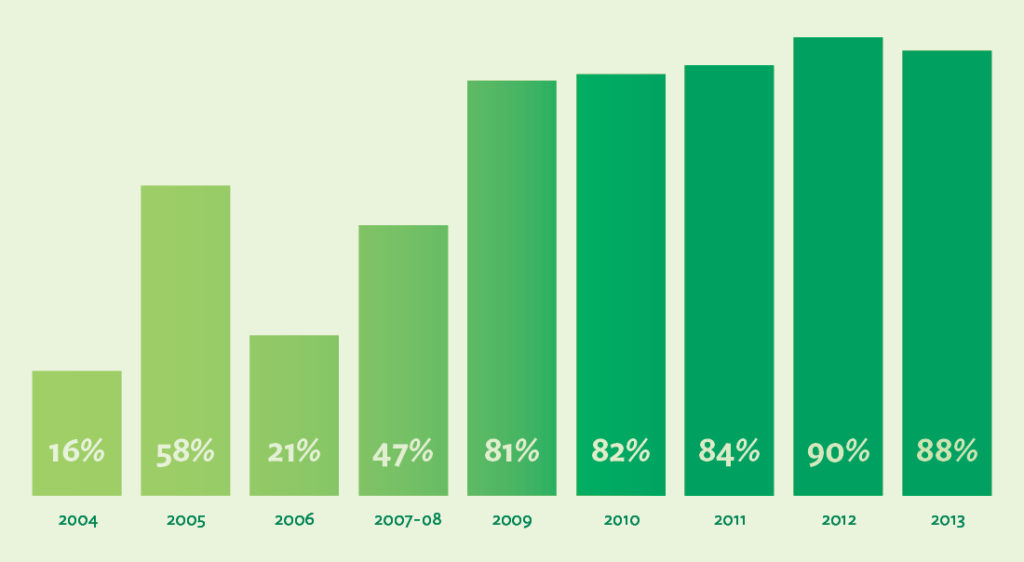

Patient Safety Survey Participation Sharply Increases

Overall staff participation in Virginia Mason’s Culture of Patient Safety survey grew from 16% in 2004 to 88% in the year 2013 alone. Affirmative answers to the survey’s key question — on whether staff speak up freely if they see something that may negatively affect patient safety — were at 80% in 2013.

Protecting Patients, Engaging Staff and Saving Costs

The Patient Safety Alert System™ at Virginia Mason is a project borne of inspiration, innovation, hard work and a dedication to always do what is best for the patient. Virginia Mason employees learn in their first day of employment that it is their duty to report anything that has caused harm or could cause harm to a patient, and the growing number of PSAs support that the organization’s culture of safety is still thriving after more than 10 years. How did Virginia Mason develop the system, and how did they embed it in their culture to continually keep patients safe? How did Virginia Mason meet its goals of dramatically better staff engagement and lower professional liability premiums—and how has the work been sustained?

Inspiration From a Factory Floor in Japan

Before the PSA system was developed, Virginia Mason’s executives viewed their organization as a quality leader that worked every day to best protect its patients. At the turn of the century, however, when they took a hard look at the data, they realized they had a lot of work to do to correct the medical errors that seemed endemic to health care in the U.S. and throughout the world.

In 2002, Virginia Mason executives were tasked with developing new ways to identify and fix the safety problems that threatened the organization’s patients every day. Gary Kaplan, MD, Virginia Mason’s chief executive officer, took them to Japan for two weeks of intensive learning to discover how Toyota had developed the Toyota Production System and worked for decades to create defect-free automobiles that were safe and reliable enough for their customers to drive. Virginia Mason’s team wondered, How did Toyota manage to increase efficiency and eliminate waste, day after day, and sustain this level of excellence?

It was on the factory floor, watching the workers stop the line and work with colleagues to fix the problems with the automobiles as soon as they were discovered, that Cathie Furman, RN, the senior vice president of quality and compliance, saw something she had never witnessed before.

We were so impressed with the [Toyota] culture—the empowerment of high-school-trained assembly-line workers who felt completely comfortable stopping a multi-million-dollar line rather than sending a defective product to their teammate,” Furman says. “That was so different from what we experienced in health care, which has historically been a very blaming, hierarchical culture.1

As much as she admired what she saw, though, she wondered if they could implement the same kind of system at Virginia Mason so that health care workers could stop a process immediately when a defect was discovered and work collaboratively to fix problems to prevent patient harm. Everyone knew that the complexity of health care meant that mistakes happened every day. Therefore, if every worker at Virginia Mason felt empowered to “stop the line,” wouldn’t that mean that the whole system would never get started again?2

Implementing a New Patient Safety System in Seattle

The leadership team knew that Toyota’s “stop the line” process could be used to keep patients safer—but they had work to do to develop it for health care. The patient safety system they’d been using for years wasn’t working well. Katherine Galagan, MD, director of clinical laboratories, said that some employees did fill out quality improvement reports, but the reports got funneled to various departments and often ended up “lost in the wash.” It was clear to everyone who had gone to Japan that they needed a new way to galvanize the right people to come together and fix the problems right away, just as they did each day on the line at Toyota.3

With careful planning, testing and implementation, the team modeled Virginia Mason’s new patient safety system on Toyota’s andon system—which enables any employee to alert managers or colleagues of quality or process defects, small or large. The development of the new system was difficult and time-consuming, and leaders discovered that a culture shift required a new focus on leader responsiveness as well as a degree of transparency that was not familiar to most of Virginia Mason’s employees.

Early on, Virginia Mason leaders agreed to support any staff member who called in a patient safety alert, even when the circumstances were charged. In a 2005 incident that later inspired employees to trust and use the system, a nurse observed that a physician did not follow protocol for a patient procedure. Because she believed that a patient could suffer harm from not following the protocol, she asked the physician to stop the procedure. When the physician refused, the nurse called in a PSA. The leader who responded to the alert thanked the nurse, contacted the physician and ordered him to stop the procedure. Surprised, the physician stopped the procedure but sharply berated the nurse for reporting the incident. The nurse then called in a new PSA, explaining the repercussions she received after acting in the best interest of the patient. The leader who responded to this new alert thanked the nurse and immediately took the physician offline. Virginia Mason thoroughly investigated the incident and provided training for the physician on the organization’s patient safety culture, which necessitated that employees need to feel safe whenever they reported an incident that they believed might cause harm to a patient. From that day forward, many employees knew that Virginia Mason’s top leaders truly respected their actions when they summoned the courage to stop the line.4

For the program to be successful, it was essential not only that employees would be supported but that the problems would get fixed. As Jamie Leviton, a patient safety manager at Virginia Mason, explains, Virginia Mason’s team set out to develop a system that would consistently encourage safety reporting and transparency, result in a rapid team response and enable leaders to address issues directly with their teams. The system was based on a team vision that patient safety begins and ends on the front line, and that reporting should be “simple, easy and intuitive.” Through years of refinements, the system became capable of enabling all employees at all levels of the organization to submit a patient safety alert by phone or online, as soon as they perceived a patient had experienced harm or could potentially experience harm.5

Results

In September 2014, Virginia Mason’s 50,000th Patient Safety Alert was reported. By the end of 2014 the average number of PSAs was 879 — a record number for the organization. The goal, promoted at meetings and on the company’s intranet, is to reach an average of 1,000 PSAs per month.

Overall staff participation in Virginia Mason’s Culture of Patient Safety survey grew, from 16% in 2004 to 88% in 2013. Affirmative answers to the survey’s question on whether staff speak up freely if they see something that may negatively affect patient safety reached 80% in 2013.

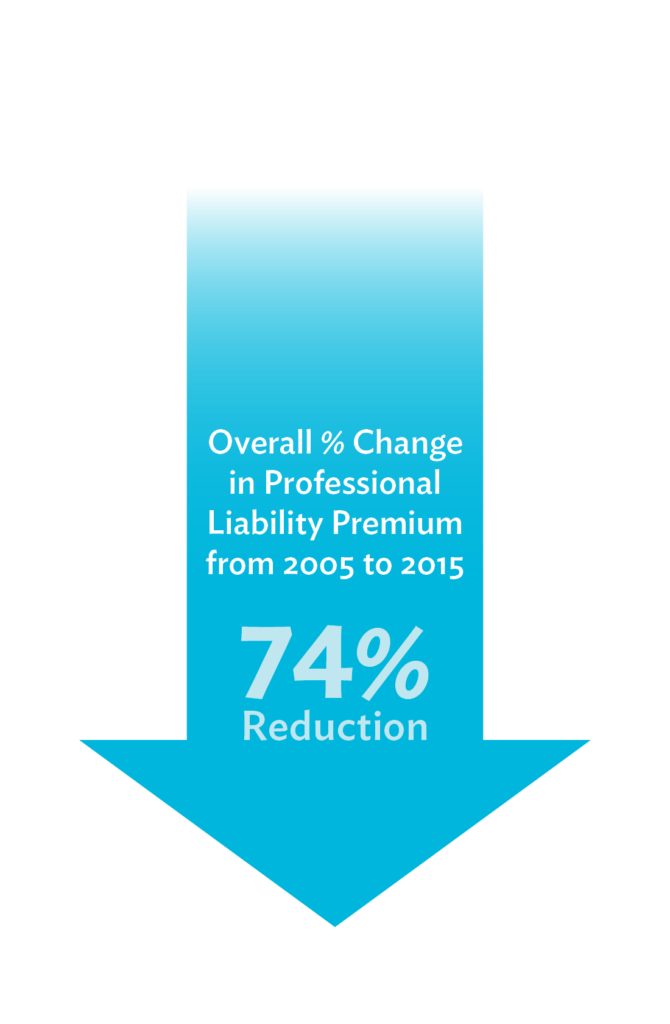

Additionally, from May 2005 to May 2015, professional liability claims saw a 74% reduction, resulting in considerable savings each year.

Continuous Improvement: Sustaining the Gains

For more than a decade, Virginia Mason has monitored the PSA system and conducted improvement events year after year, with all levels of staff, to make it better. Here are the top key components contributing to the PSA system’s sustained success:

Employees feel safe reporting a patient safety event, near miss or potential problem. For employees to feel safe, they must experience a culture of respect in the workplace. Leaders are responsible for promoting and embodying a culture in which employees feel safe not only speaking up about barriers to patient safety but also voicing and following through on ideas for improvement.

Year after year, the organization’s leaders continually look for ways to keep the program going strong. In 2011, leaders and providers were inspired by Lucian Leape’s powerful presentation at Virginia Mason on the tie between respectful behavior and patient safety—and they knew that they had more work to do to empower employees who still did not feel safe making a PSA. Lynne Chafetz, general counsel at Virginia Mason, said that Leape discussed “not just the obvious—surgeons throwing instruments across the room,” but also “the disrespect that’s more covert.” She knew, and others in the audience also knew, that creating a deeply respectful culture was necessary to empower every employee to speak up for patient safety. That’s when Virginia Mason developed a Respect for People initiative to make the organization’s culture feel even safer for employees.6

Every PSA is important. In the early years, the PSA program was complex, and it required extensive training throughout the organization to take hold. Later Virginia Mason’s leaders realized that if they wanted staff to report any potential threat to patient safety, no matter how small, they had to make this known. In the Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Public Safety, Furman and Robert Caplan, MD, discussed the program’s dramatic results both in the terms of number of safety reports and the time it took to fix the problems. They also said that to achieve these benefits, the organization needed to keep the door open to all safety concerns. After all, whether a safety concern is “significant” depends on the point of view of the reporter—and no act of speaking up should be dismissed until the matter is investigated and leaders know that patients are safe.7

For example, Brenda Simon, an organizational development specialist in human resources, relates how even a nonclinical employee at a health care organization can—and should—be a patient safety inspector:

One day I was walking down a stairwell in one of the hospital buildings and noticed that a long strip of yellow tape on one of the steps had come loose. I immediately thought that a patient or team member might trip on this step, so I called in a PSA and explained the situation. When I took the stairs the next day, I saw that the tape had been fixed. All of us are called upon to be on the lookout for threats to patient safety, so I was doing my part—just as the rest of my 5,000 colleagues do every day.8

Gary Kaplan reinforces the importance of each report when he speaks to staff and to other organizations. He emphasizes the dual benefits of PSAs: “Each patient safety alert not only protects the individual patient, but gives us the opportunity to improve our processes in real time to assure the safety of every patient, every time.”9

Staff can self-report a PSA without punitive consequences. One of the main differentiators of a lean system—whether it’s in manufacturing or health care—is that a defect signals there’s a problem not with the employee engaged in the procedure but in the organization’s processes that care for its patients. Therefore, it stands to reason that if an employee realizes that his or her own actions have caused harm—or could cause harm—to a patient, then that employee should be able to make a PSA on the incident without punitive action. In one instance, Henry Otero, MD, reported a PSA after his colleague told him a cancer patient’s magnesium level was low. “I didn’t know how I missed it,” Dr. Otero said. “But I realized it’s not about me, it’s about the patient. The process needs to stop me [from] making a mistake.”10

Staff are supported when they make a PSA after an adverse event. Virginia Mason expects all staff to call in a PSA as soon as any patient suffers an adverse event, and they know that the way leaders respond to PSAs is crucial to keeping employees engaged and helping them see the process as personally meaningful. For every PSA after an adverse event, the leader who responds to it sincerely thanks the employee for reporting and may engage the employee to talk through the incident to help assess the level of urgency and determine next steps. For some PSAs, though, the support goes further. In a survey response, one physician recalled what happened after he called in a PSA:

Last November I undertook an emergent after-hours procedure which tragically ended in a fatal outcome. That morning I filed a PSA as a matter of course and I was surprised when I received a rapid response from the on-call PSA staff member. She facilitated providing support for the family and me that day as well as in the weeks afterwards. The support process was a much appreciated contribution at that challenging time.11

Leaders support it. When an employee makes a PSA, the senior executive who is responsible for the area responds by ensuring that patients are safe as soon as possible and instigating a team effort to make the targeted process defect-free. Executives learn about patient safety issues in another way, too—by daily rounding. As they meet with staff on the front line, they ask if they know of any instances of patient harm, near misses and ideas for improvement. The leaders take those ideas and determine whether a process needs to be stopped or a worker needs to be taken offline during an investigation. Kaplan emphasizes that executives can’t simply let go of the process. As he says, “Every staff member can and should be a quality and safety inspector, but [he or she] will only do that if that work is supported 24-7 by the executive leadership.”12

And because the PSA system is central to Virginia Mason’s patients-first culture, no one is surprised when a process is halted for the good of patient safety. As Denise Dubuque, surgical and procedural services administrator, recalls after one PSA, “We escalated an issue and the senior leaders stood behind the team. The staff saw that they were listened to. It was pretty powerful.”13

Board members support it. When PSAs are reported, notices are sent to Virginia Mason’s board members. Whether it’s a physician’s error that is quickly corrected or a billing mistake that delays care for a patient, the board members get involved to ensure that leaders and staff are addressing the problems in ways that best support the organization’s patients.

When anything goes wrong at Virginia Mason, says board member Julie Morath, I know immediately what happened and what is being done. Those events are not closed until the board says they are. This is not a rubber stamp board.14

Staff are part of the improvement process. After a PSA is called, leaders use root-cause analysis to determine whether the incident stemmed from a process problem, an individual error or a behavior issue. “Once you realize what the components are in a patient-safety alert, you can deal with correcting them,” says Lucy Glenn, MD, chair of Virginia Mason’s radiology department.

When a PSA reveals that intensive improvement work must be done to correct the problem and keep patients safe, leaders form teams that work in the affected areas. Richard Lee, administrativ director of radiology operations, describes the way leaders begin the process of engaging staff in the improvement work:

We go to the people who are actually doing the work and are in immediate contact with the patients. We have a process where we ask them to generate ideas as to what could be improved, and that’s where it starts—from identifying how our processes could be made better for the patient.15

Staff are engaged not only from the beginning, but in subsequent meetings, improvement events, testing, implementation and sustainment.

Individuals and teams are recognized. Even in a culture in which employees are told that they’re expected to speak up for patient safety, the act of actually reporting a PSA can seem risky or overwhelming for some. That’s why the organization’s leaders work hard to respond quickly and positively to employees who report—with thank-yous from supervisors and executives; a monthly Good Catch Program, in which a single employee is recognized for a PSA that led to an exceptional solution; and the Mary L. McClinton Patient Safety Award, which is given annually to the team who has done the most to improve patient safety. This last type of recognition is especially meaningful to employees because the event not only commemorates the tragic death of a beloved patient in 2004, but also marks the time when executives chose to be transparent about the error to the staff and the press. Even more, it solidifies the organization’s fervent commitment to make health care safer for all their patients.16

Feedback continues to make it better. Since the start, the PSA has evolved to make sure the engagement and response time continue to improve. In August 2015 the PSA system introduced easier navigation to enhance reporting. “We made these changes based on feedback from team members, who told us they wanted a simpler reporting system and a way to track how their PSAs are being handled,” says Leviton. “This new version delivers on both requests.”17 Additionally, as a way to continue the engagement, leaders and staff were invited to sign up for training sessions to learn about the details, ask questions and continue to keep patient safety at the forefront of their work every day at Virginia Mason.

References

2. Kenney C. Transforming Health Care: Virginia Mason Medical Center’s Pursuit of the Perfect Patient Experience. New York: CRC Press; 2011.

3. Ford A. From bottom to top, a culture of safety.

4. Kenney C. Transforming Health Care: Virginia Mason Medical Center’s Pursuit of the Perfect Patient Experience.

5. Leviton J, Valentine J. How risk management and patient safety intersect: Strategies to help make it happen. Patient Safety Blog. National Patient Safety Foundation. March 24, 2015. Accessed September 9, 2015.

6. Kenney C. A Leadership Journey in Health Care: Virginia Mason’s Story. New York: CRC Press; 2015.

7. Furman C, Caplan R. Applying the Toyota Production System: Using a patient safety alert system to reduce error. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007; 33(7): 376-86.

8. Interview with Brenda Simon, August 17, 2015.

9. Begasse T. Patient safety draws national, local experts to NavHosp Jax. Jax-Air News. March 7, 2012. Accessed September 9, 2015.

10. Allen N. Can the Japanese car factory methods that transformed a Seattle hospital work on the NHS? July 3, 2014. Accessed September 9, 2015.

11. Kaplan G, Furman C. Promoting safety: Creating the culture needed to achieve system improvement. Presentation at the International Forum on Quality and Safety in Healthcare. April 24, 2015.

12. Rowe M. If it ain’t broke, fix it. HealthLeaders Magazine. December 13, 2007. Accessed September 9, 2015.

13. Plsek P. Accelerating Health Care Transformation with Lean and Innovation: The Virginia Mason Experience. New York: CRC Press, 2014.

14. Kenney C. A Leadership Journey in Health Care: Virginia Mason’s Story.

15. Vasko Cat. Waste not, want not: Inside the Virginia Mason Production System. Radiology Business. July 10, 2012. Accessed September 9, 2015.

16. Plsek P. Accelerating Health Care Transformation with Lean and Innovation: The Virginia Mason Experience.

17. Virginia Mason internal communication. Upgraded PSA system up and running: Check it out! August 12, 2015.