Case Study | Surgical Setup Reduction Improves Patient Outcomes

To be financially viable, a hospital’s operating rooms (ORs) must keep quality and utilization high and expenses low. It’s critical to plan ahead, be prepared, and set volumes correctly. This means an organization’s OR team should be continuously finding ways to improve turnover time in their ORs, while also sustaining improvements to patient safety, staff engagement and organizational costs.

Surgical instrument processing is critical to safe, high-quality surgical care but has receives little attention. Typical hospitals have inventories in the tens of thousands of surgical instruments organized into thousands of instrument sets. The use of these instruments for multiple procedures per day leads to millions of instrument sets being reprocessed yearly in a single hospital. Errors in the processing of sterile instruments may lead to increased operative times and costs, as well as potentially contributing to surgical infections and perioperative morbidity.

When Virginia Mason’s team examined their inventory of surgical instruments they saw, that at any one time, thousands of instruments were being used and processed during setup, surgery, breakdown or sterilization — about 5.2 million instruments per year — and still large amounts of instruments were left unused in storage. Additionally, there were roughly 3,800 unique instruments sets set to different surgeries and different physician’s preferences. Although they had worked hard to keep the inventory down,3 they knew innovative thinking could help them make lasting improvements.

A quality monitoring approach was developed to identify and categorize errors in sterile instrument processing through use of a Daily Defect Sheet. Virginia Mason Production System® (VMPS®) improvement methods were used to improve the quality of surgical instrument processing through redefining operator roles, alteration of the workspace, mistake-proofing, quality monitoring, staff training, and continuous feedback.

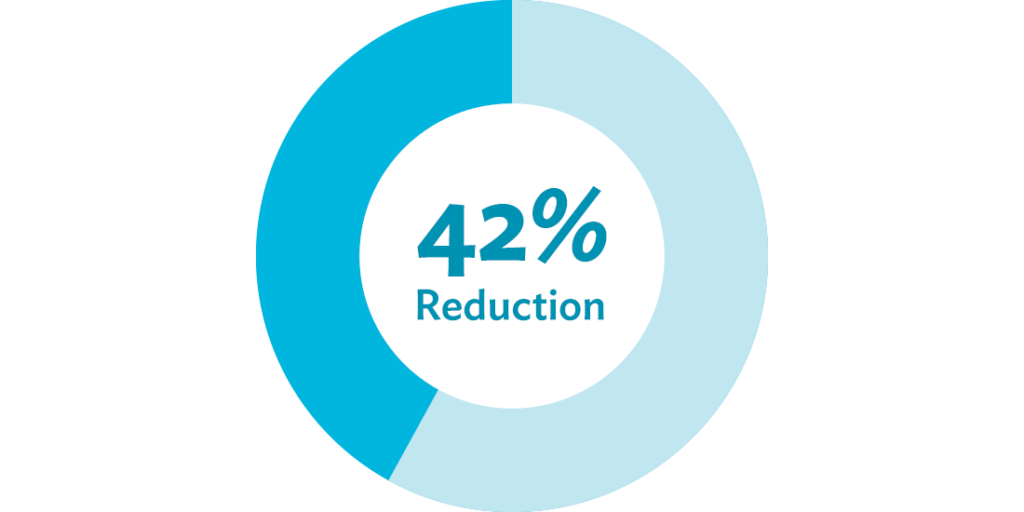

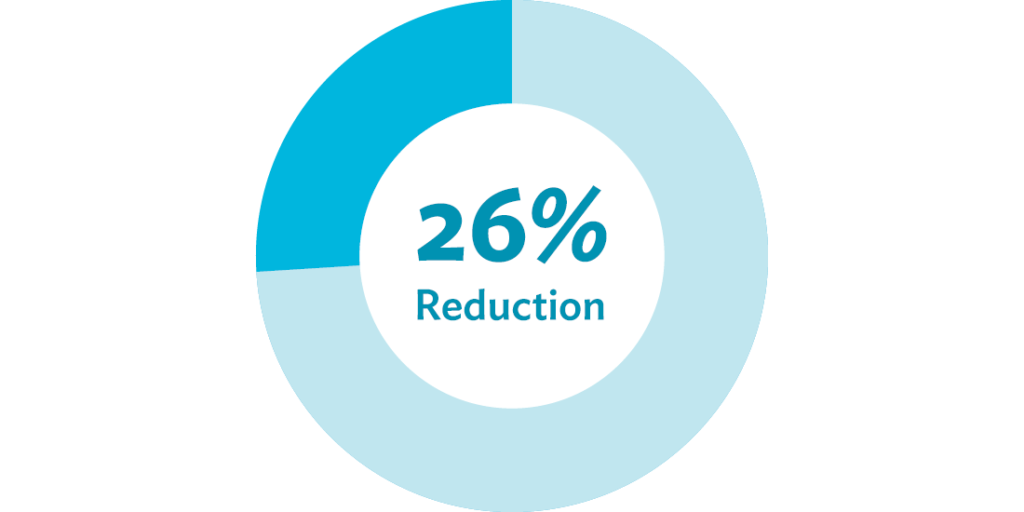

To study the effectiveness of the quality improvement project, a before and after comparison of prospectively collected sterile processing error rates during a 37-month time frame was performed. After implementing a transformation to their operating rooms’ build-to-order (BTO) process, they removed 58,728 unnecessary instruments, and eliminated all $500,000 worth of unused “sleeping” sets — weighing 29,480 pounds — from processing in the first year. In neurosurgery alone, instrument assembly time decreased by 42 percent, and inventory was reduced by 26 percent.

Instrument Assembly Time

Inventory

Starting with inventory, progressing with data collection

To answer the question of which instruments surgeons needed most or preferred to use, the team examined and collected surgeons’ preferences based on actual usage. The vision, according to the director of sterile processing at the time, was to create a “better patient experience, with fewer defects, faster setup and better patient throughput.”

Team leaders — after evaluating their employees’ interest and aptitude — trained a nominated group of surgical technicians in VMPS® improvement tools and methods. Following the training, the group took their clipboards, pens and timers to operating rooms, setup areas, breakdown areas, sterilization rooms and storage rooms. They observed the different work areas to understand physician priorities and track how much time was spent on tasks that made a difference to patients and staff versus time spent on wasteful processes that didn’t benefit patients and overburdened staff.

The improvement team was able to easily step into the operating rooms, introduce themselves and explain what type of data they’d be collecting. The work was transparent from the beginning, and no one felt threatened or worried. The surgeons and staff knew they were all a team and that the improvement team was there to improve work for patients and staff alike. They observed each surgeon and procedure five times, building data so that the team could truly understand the current state and begin planning for a better process to test.

Establishing a structure to guide the work

Armed with data, team members came together for a 3P (Production Preparation Process)4 workshop to set their vision for a dramatically more efficient process. By the end of the 3P, the participants had created a guiding team to determine next steps, oversee all the work and answer any questions that came up throughout the process. The guiding team included a sterile processing leader, operating room leader, improvement office leader, neurosurgeon, surgical technologist, sterile processing technician, project support staff member and administrative support staff member.

Using improvement methods and tools to get results

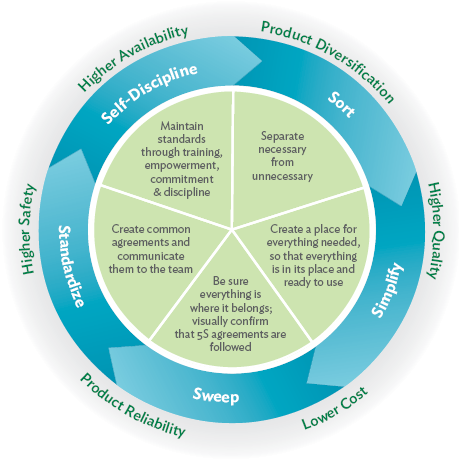

Next, the team employed the concept of 5S (sort, simplify, sweep, standardize, self-discipline). They discovered that almost 60 percent of the items in their orthopedic case sets were rarely used. This equates to 700 tons of unnecessary instruments being processed, per year. Using data, they sorted which instruments were being used, and simplified the process by removing non-critical instruments left unused. They swept the area by designing a repeatable inspection of case sets, standardized their tray layout, and established a team agreement to continue monitoring.

The creation of the build-to-order instrument sets employed the concept of just-in-time inventory — in which just the right surgical instruments would be delivered just when they were needed — and allowed for customization to each surgeon’s needs for a procedure. The new setup technique made the process of tool assembly much easier for surgical technologists. A production board provided team members with a visual reference of the current demand for supplies.

In an additional improvement event, focusing on the setup for craniotomy procedures, participants discovered how to customize each set, reducing the setup time and the OR space needs in the suite. By the end of the event, they were able to combine sets, reducing their setup time from 34 minutes to 2 1/2 minutes, a 92 percent reduction. The team compared times before and after the improvement events and found that the more limited case sets did not increase overall procedure time but greatly increased OR turnover time.

Seeing financial gains

This work also yields significant financial benefits to a health care organization. A reduction in processing yielded an annual cost savings of $65,000 per year. The number of lost, broken and damaged instruments was also reduced.

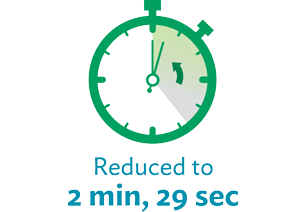

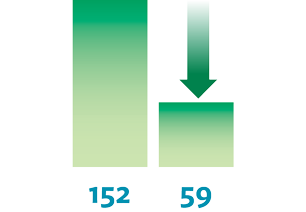

Getting results for other surgery sets

The team spread the work by helping other specialty teams, including orthopedics, neurosurgery and thoracic surgery produce similar setup reductions. The results for improving the laminectomy surgical setup were very impressive. After implementing the build-to-order sets, the instrument assembly went from 34 minutes to 20 minutes, 15 seconds. The instrument setup in the OR went from 24 minutes, 9 seconds, to 2 minutes, 29 seconds — a 90 percent decrease. The number of instruments used decreased from 152 to 59, and the number of instrument sets decreased from 5 to 2.

Instrument

Assembly

Operating Room

Instrument Setup

Number of

Instruments

Improving quality and safety

During the assessment of their instrument inventory before the improvement work, the team determined that the large number of unnecessary instruments in storage could have a big impact on safety. Not only was the probability greater for a surgical technologist to select the wrong instrument for a procedure, but the time spent searching for specific instruments and maintaining all these instruments — many of which were processed and sterilized yet never used — could potentially affect patient care.

Before the intervention, instrument processing errors occurred in 3.0 percent of surgical cases, decreasing to 1.5 percent. Improvements were observed in multiple categories of error types, particularly the assembly errors of packaging (from 0.66 to 0.24 errors per hundred cases), and foreign objects (0.17 to 0.02 errors per hundred cases).

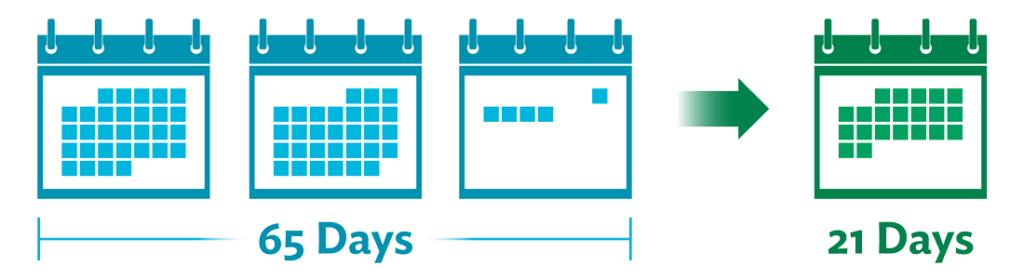

Improving patient access and timely care delivery

The lead time for booking orthopedic surgery, for example, went from 65 days down to 21 days. This meant surgeons did not have to wait as long between procedures and could handle an increase in volume of patient cases.

Key takeaway

Surgical instrument processing errors are a barrier to the highest quality and safety in surgical care but are amenable to substantial improvement using improvement techniques.

Originally published May 24 2018, updated July 12 2021

Are you ready to develop advanced process improvement expertise?

Learn more about our virtual intensive certificate program – Advanced Process Improvement Training.

“This course work came in at the perfect time as the topics we covered in class aligned perfectly with a vaccine delivery clinic we created and we used almost every tool taught 100% to deploy something outside of our comfort zone, and it was wildly successful!” – Chuck Hampston, Lean and Process Improvement Coordinator, Memorial Medical Center, Ashland WI

References

2. Cendan JC, Good M. Interdisciplinary work flow assessment and redesign decreases operating room turnover time and allows for additional caseload. Arch Surg. 2006; 141: 65-69.

3. King R. How can standardizing surgery tools prevent adverse events? Virginia Mason Institute website. https://www.virginiamasoninstitute.org//how-can-standardizing-surgery-tools-prevent-adverse-events/. Published February 25, 2016. Accessed August 24, 2016.

4. Backous C. Using a 3P to create a vision and plan for better patient care. Virginia Mason Institute website. https://www.virginiamasoninstitute.org//using-a-3p-to-create-a-vision-and-plan-for-better-patient-care/. Published July 20, 2016. Accessed October 4, 2016.

5. Farrokhi FR, Gunther M, Williams B, Blackmore CC. Application of lean methodology for improved quality and efficiency in operating room instrument availability. J Healthc Qual. 2015; 37(5): 277-286.

Virginia Mason Institute. Respect for people: a building block for engaged staff, satisfied patients. Virginia Mason Institute website. https://www.virginiamasoninstitute.org/respect-for-people-building-block-for-engaged-staff-satisfied-patients/. Published January 16, 2013. Accessed October 4, 2016.