How Eliminating Wasteful Processes Helped a Team Deliver the Perfect Patient Meal Tray

An interview with Megan McIntyre

Why is waste elimination so important to delivering quality care?

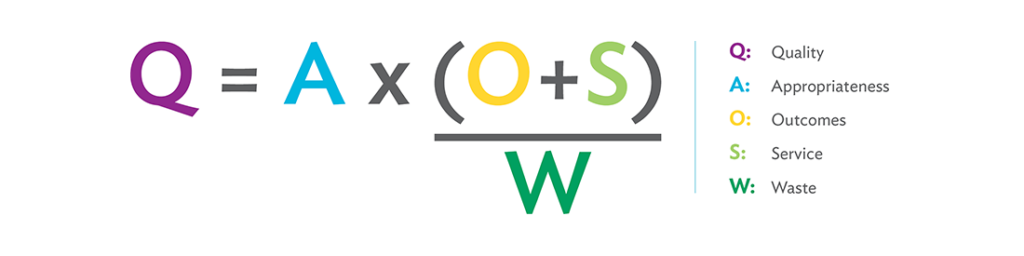

MM: Waste elimination is essential to the Virginia Mason Production System (VMPS) and lean methodology. The waste in health care prevents us from achieving our strategic plan and delivering the highest quality of service. In the VMPS waste equation [see image below], we have intentionally made a point to show that waste is a drain on quality by including it in the denominator.

Waste detracts from service or experience and certainly taints the outcome. When we consider a health care process from a hospitalized patient’s point of view, we can find many elements that are frustrating for them and out of their control.

How can waste be measured in health care?

MM: At Virginia Mason there is a daily focus on the identification and elimination of waste as part of everyday work as well as its impact on experience. It’s also important in the preparation for formal improvement events and as an actual measured process target. We look at waste when we’re working to improve quality and reduce lead time, inventory, space and transportation time and expense, and we measure the impact of waste on patient experience using our experience-based design methodology. Virginia Mason has hundreds of examples of how focusing on waste has increased quality in sepsis care, joint replacement procedures, delivering test results, facility design, finance operations and so much more. The more you look at waste from a patient’s point of view, the more you see what can be improved.

Can you give an example of waste that can be discovered by looking from a patient’s perspective?

MM: For some patients, meals are something — and maybe the only thing — that they can control and look forward to. Even with restricted diets, patients still expect to have the right meal delivered at the right time. It can be as complex as an allergen-free multicourse meal or as simple as a cup of hot coffee (which can feel critical in Seattle). Clinicians also expect that the appropriate food items and presentation will be provided to patients in a way that doesn’t compromise their care — with foods thickened for safer swallowing, for example, or fasting timed before certain procedures or blood sugar measurements.

By removing waste and improving the process of delivering the perfect patient meal tray from the time the meal is ordered until its delivery, a health care organization’s food-service team can impact the patient experience by serving the right food at the desired temperature. They can also avoid the negative outcomes of serving a meal that contains foods outside of a patient’s prescribed plan or in conflict with a procedure, test or medication administration.

“The complexity of delivering the perfect tray to the patient was hard, given the infinite number of order combinations, multiple dietary restrictions, patient preferences, coordinated efforts with medication administration or procedure timing, and the significance of food as a marker for a change in patient health status. At times it all felt so big, especially when I observed the patient experience firsthand and quantified the gap between the current state and the ideal state.”

– Megan McIntyre

How has Virginia Mason’s food-service team used the concept of waste elimination to improve the patient experience?

MM: I had the opportunity to work with Virginia Mason’s food and nutrition team for several months on improving the food-delivery processes. We focused a portion of this work on improving the process of delivering meal trays to patients. At Virginia Mason, our patients have access to an on-demand meal service, where they can order from a variety of menus, similar to hotel room service, instead of being served at fixed times with fewer meal options. The process had limitations and challenges.

In the spring of 2016, I was the team leader for an RPIW (rapid process improvement workshop) that focused on using the VMPS concepts of mistake-proofing, visual controls and one-piece flow to build and deliver a perfect meal tray for every patient, every time. For about half of the team members, this was their first formal process improvement event, but that didn’t slow them down — the team was engaged and action-oriented during the entire week.

Their outcomes were fantastic. They decreased the percentage of trays that took longer than 30 minutes to deliver during peak meal times, going from a baseline of about 50 percent to 30 percent after day three of the event. The lead time during peak meal service at subsequent remeasures dropped from about 40 minutes at baseline to just under 30 minutes. The most exciting outcome of this work was the percent of negative inpatient comments regarding food temperature and timeliness. In fact, the standard hospital satisfaction survey showed a drop from 32 percent at baseline to zero percent, even several months into the new process.

How did the team know what to improve?

MM: The pre-improvement value stream map that our team created identified several opportunities for improvement. Here are three:

- Patient orders were delivered to floors in batches based on the size of the delivery cart and the availability of a delivery person.

- Defects, including missing items, undesirable temperature (such as hot foods arriving cold), or deliveries made outside of the expected delivery time frame, were often caught by the patient. Correcting the defects for the patient resulted in rework for multiple operators.

- The person working as the expeditor was frequently interrupted on the production line.

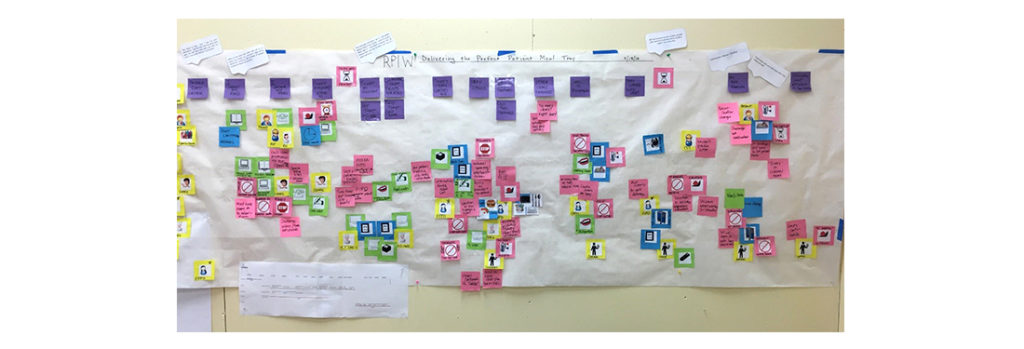

During data collection, the team reviewed patient satisfaction data and interviewed employees to create a process flow map, which is pictured below. The pink sticky notes represent defects, waste or opportunities. My favorite part? The home team contributed defects and waste opportunities to the map with no finger-pointing.

During the course of the event, the team used idea generation, root-cause analysis and PDSA (plan-do-study-act) testing to tackle the problems. Two examples stood out.

First, the team recognized the waste that was generated via the batch delivery process — they saw that time, processing, transportation and defects led to overproduction and remaking food orders. The solution they created, tested and implemented involved two parts. They set the expectation that a delivery cart will contain no more than three trays, which prevents the initial tray from waiting. They also used a visual countdown timer to signal when tray waiting time exceeded five minutes. The timer alerted the expeditor to send the cart regardless of the number of trays (except when empty), which proved helpful during very busy times. Sending the delivery staff out with fewer trays resulted in short delivery cycle times, reduced work-in-process and ultimately less waiting time for patients. The delivery staff also reported feeling less rushed when interacting with patients. Together, the team discovered that in processes where some amount of batching is required, they should work toward the smallest batch possible and not let something arbitrary, such as cart capacity, determine the batch size. In the team’s words, “the domino effect of moving towards smaller and smaller batch size” not only decreased errors but also decreased the burden of work on staff, with “less effort needing to be spent on routing and sorting.”

Second, the team identified that the task of pouring cups of coffee to add to the delivery cart created delays in delivery. Despite the small delivery size, the coffee was not arriving at the desired temperature. They tested a few different methods on their PDSA form, including the use of a carafe and an airpot brewer. What really impressed me was how the team was concerned for the delivery person’s safety with the measurable change in coffee temperature. From the time the coffee was poured in the central kitchen until it was delivered to the patient room, the temperature could decrease by almost 20 degrees Fahrenheit. The best result, which they implemented, occurred when the delivery person poured the coffee using a securely mounted airpot, just outside the patient room, to ensure that the coffee arrived hot.

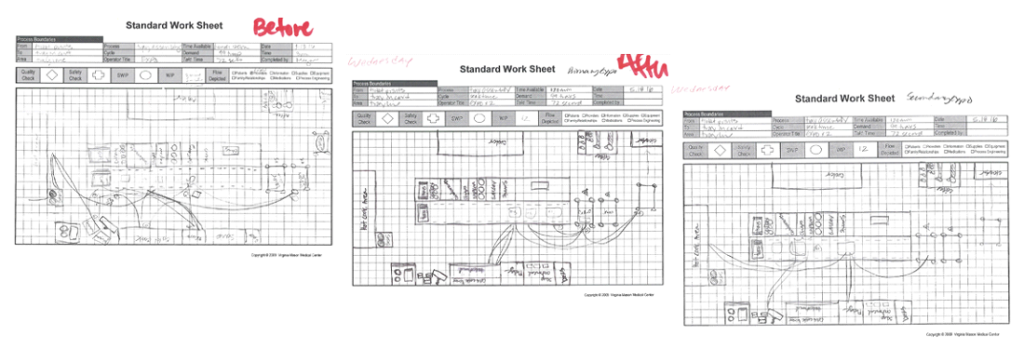

The team also did focused improvement work around defining the role of the expeditor, creating a secondary expeditor position during peak time to focus on tray setup and empowering the first expeditor to manage the flow of patient food orders. Frequently, team members would want to jump in and help during busy times, but the help ended up creating distractions and delaying delivery runs. They realized that it’s good that people want to help, but the lead time decreased and the quality increased after the team created and reinforced standard work and expectations. The expeditor’s role evolved into one that prioritized tickets, performed quality and safety inspections on trays, and kept the process moving.

I could go on and on about the great work our food and nutrition team has done at Virginia Mason beyond this important process. I find their connection and focus on the patient inspiring.

What was the hardest part of working on this process?

MM: Besides the intoxicating smell of bacon every morning, the complexity of delivering the perfect tray to the patient was hard, given the infinite number of order combinations, multiple dietary restrictions, patient preferences, coordinated efforts with medication administration or procedure timing, and the significance of food as a marker for a change in patient health status. At times it all felt so big, especially when I observed the patient experience firsthand and quantified the gap between the current state and the ideal state. Seeing the gap reinforced W. Edwards Deming’s observation that the design of a system is the cause of what the system ends up producing.

Did you find anything especially memorable about this team’s work?

MM: Yes! One of our team members was a Virginia Mason board member. She was able to bring her professional experience in catering, as well as her experience as a patient, to our work during the week by creating and pilot-testing service standards for delivering trays. She also created a tool for leaders to solicit timely patient feedback. Virginia Mason’s board is included in our improvement work in ways that are not typical of most health care organization boards, and this makes a big difference to our work and the board’s work. I was really happy to collaborate with her.

Another memorable experience is that the team came up with great analogies for how their work improved. Before the event, they said the expeditor’s role seemed like “herding cats.” By the end of the event, they agreed that the role was more like that of an air traffic controller. And in their summary of the changes they implemented, a team member reported: “Small but significant improvements are like clearing out a log jam. By shaking out the debris, you clear the way for more to happen.”